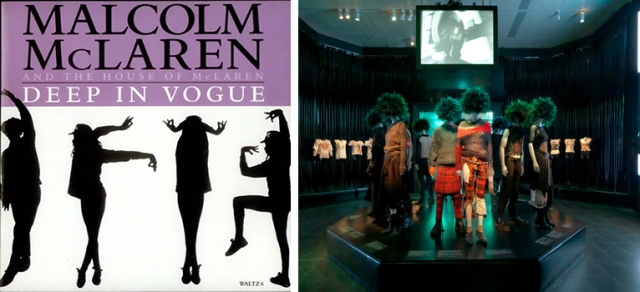

Music icon Malcolm McLaren (he died in 2010) was an integral early element in multiple counter cultures and upcoming genres throughout his career. In the late 1980s he helped spearhead the mainstream knowledge of the New York drag ball scene with his song “Deep in Vogue” that came out a year before Madonna recorded her own ode to the highly flamboyant freestyle dance concept. He was even an early figure in modern fusion of pop and opera (“popera”?) with his album Fans, and turned the rhythmic beats of street chants into vibrant and electric dance music with tracks such as “Double Dutch”, “Buffalo Gals”, and “Something’s Jumpin’ In Your Shirt”. Personal preferences aside (“Deep in Vogue”, “Double Dutch”, and “Madame Butterfly” are rather astonishing feats of divine pop), this obviously all takes a back seat to his most famous addition to global counter culture: punk.

Image one //

Image two source //

The punk movement acted as a shot of revolution to the British youth population and an early seed to several different alternative cultures around the globe. Along with Vivian Westwood, his girlfriend at the time and now a famed couture fashion designer frequently worn by Helena Bonham Carter and seen in TV and movies like Sex and the City, the two turned offensive slogans and imagery into high art fashion that simultaneously enraged and engaged. The fashions that they sold in their boutique SEX on Chelsea’s King’s Road revelled in imagery of nudity and the power of language. Clothes were frequently emblazoned with images of naked men and one of the most famous, named “Tits”, is simple an image of a pair of breasts on a plain white tee. Others use words like “sex” and “rape” to evoke shock and outwardly express a generation’s contempt at an oppressive society.

All of these and more are part of the new Punk: Chaos to Couture exhibit currently at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Quite apt that this particular museum sits on the west side of Fifth Avenue, infringing upon the boundaries of the elegantly constructed and designed Central Park since that is exactly what the punk movement did to the fashion and societal establishment in the 1970s. It infringed on a world that was so carefully designed to the idea of perfection. Depending on where you stand in the park, the museum’s architecture rises out from the leafy surrounds like a sore thumb, catching the eye of anybody walking by. It’s out of place and doesn’t belong, just like punk once did. Also like the museum, punk was eventually accepted and is now a permanent fixture and now with this exhibit is officially respected as an artistically and culturally important moment in history.

Image one and two source //

Entering the exhibit and you’re instantly confronted with a recreation of the dirty, muck-strewn bathroom of famous New York punk club CBGBs. It’s certainly a mood setter if ever there was one and I instantly recalled Adrian Brody’s character in Spike Lee’s Summer of Sam (1999) who performs at CBGB’s rather than the more fashionably popular discotheques and how his newfound punk persona and radicalised hairstyle is seen as a symbol of evil. A circular runway of famous McLaren/Westwood designs as well as another set recreation – this time of their SEX shop – and detailed history of their work and its cultural significance before diverting into some of the more high end interpretations of the punk aesthetic. Designers like Michael Kors, Dior, Calvin Klein, Burberry, Balenciaga, and even Chanel are present with designs that incorporate distressed materials, leather, safety pins, spikes, clips, and hooks alongside more traditional silhouettes and shapes. Westwood’s designs are clearly the more dangerous and risqué, but there’s an almost equal element of high-end danger in the runway interpretations.

The exhibition then continues along the same lines looking at how designers have taken the principals of punk and applied them to fashion that is both accessible and red carpet ready as well as experimental and avant garde (such as the garbage bag designs of Gareth Pugh).

Special mention must be made of the installation’s production design that uses grungy brick aesthetics with a stylish, slick black colour scheme. It’s a real visual treat that is in stark contrast with similar exhibits that I have seen both here and back home in Australia. The exhibition producer must be applauded for giving the display a polished, up-class look when it could have very easily been dismissed with simple white walls. More attention could have been applied to the actual music that went so hand in hand with the fashion movement, and was the reason for its rapid ascension. A few small screens playing some sort of indecipherable video wasn’t enough for my liking, nor was the lack of information and context regarding the high fashion punk looks that make up the majority of the exhibit. Minor complaints, possibly, but given the strength of everything else they are frustrating and easily fixed. Still an otherwise fabulous ode to a misunderstood and underestimated segment of history.